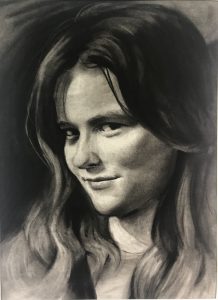

Autohypnosis by: Maddison Authur, Charcoal, 2018

At twelve thirty exactly Abby finally made her way downstairs. She was still wearing those horrid, grey pajamas as she trudged into the kitchen, where breakfast had already been conducted and finished. Though the dishes from the event still awaited her arrival in the sink. She pulled down a clean porcelain bowl and grabbed a box of sugary, processed cereal. I sighed to myself, but sound traveled very well in the living room, so when Abby turned towards me from behind the countertops with an unspoken question I simply continued to read my magazine.

I looked at the clock, for it was set above me on the fireplace mantel.

“Good afternoon, dear,” I called.

“Afternoon,” she answered hesitantly, which was odd since she should be well rested.

“Does your alarm clock need new batteries again?” I asked to simply make conversation.

“No,” she sighed. I looked up from my place on the loveseat, taking in her appearance.

“Is today laundry day? Do you need some help with the wash?” I offered my assistance out of pure generosity.

“No but thank you for the offer.” Abby breathed, as though exasperated.

“Oh honey,” I interjected as I watched her pour milk from the jug into the bowl filled with floating, chocolate pieces, “I believe there is still some salad, leftover in the fridge.” Abby stalled for a moment, staring down at the small bowl in front of her. Hopefully debating.

“Okay, thank you for telling me,” She responded finally with a huff. I nodded, satisfied with myself.

“Just letting you know, dear,” I added before continuing with where I left off on the page of my magazine.

“Did you really have to tell me though, Mom?” She stood at the edge of the kitchen, just where the tile meets carpet. I looked up at her, for I had to readjust as to not lose my place in the article I was reading.

“Pardon, dear? I did not catch that.”

Abby shuffled her feet, switching her weight between her hips. That must have been strenuous. “I asked,” she began again, “why did you have to tell me about a salad, when you clearly saw me making myself cereal.”

I frowned, was it not obvious? “Only to bring it to your attention, since you slept in so late and failed to join your father and I when we had breakfast already.” Honestly, my daughter’s mood swings are a sight and so uncalled for. I was only thinking of her well-being. She always seems to miss the variety of choices I usually pack the fridge with.

“Whatever, forget it,” she murmured. Her shoulders slouched inwards–that was not a flattering figure–and then she traveled to the kitchen table where her “meal” was placed.

“Did I ever tell you about when I was young?” I called out to her behind me, already reaching for my high school’s yearbook. I carried it over to join Abby at the table and opened it up to a random page that was dog eared in its corner.

“Yes, more times than I can count,” but Abby was mumbling, so I hadn’t heard her.

“Oh, look here. This is when I was crowned queen at my prom.” I scanned the page of iridescent glitter decorations and ran my fingers over the indents of multiple scrawls of autographs from my past admirers. I turned the page. “And here I am giving my inauguration speech as student council president in Irving High’s old gym.” I giggled to myself as I remembered how that day went. “I had to borrow one of my mother’s suits that day. It was her best one too.”

“Let me guess, the one with lace?” Abby continued to mumble. I gave her a look, for it was rude to talk when someone was already talking.

“The lace trim added such an elegant touch; it was a beautiful ensemble. And we wore the same size, four, so it all worked out. I had that election in the bag, but I guess it helped to be known as cheer captain as well.” I reminisced with tenderness.

“Because Cheerleading is definitely an academic credential.” Well, at least she waited until I finished. But, mumbling nonetheless, which is equally rude.

“It would’ve been nice to do the same, as in sharing clothes I mean.” Abby’s chair screeched across the tiled floor as she stood abruptly. I flinched at her mannerisms. “Abby, what did I say about the chairs. You will leave marks,” I reprimanded her. I only keep saying these things because she always seems to forget.

“Sorry.” Her answers were always so short and curt, but I could not be upset. For I was the one who warned her that a young lady should try not to be too bothersome with lengthy words.

“Is something the matter, dear? You seem to be a bit blue today.” I swear teenagers are always in a constant flux of emotions. I do recall being moody myself, but for Abby it seemed like smiling was a curse. Sometimes it was hard to tell that she was my daughter, but our explosive red hair usually gave it away. But, while mine tended to maintain its vibrant and alluring nature, Abby’s resembled that of the after effects of an actual bomb.

“When I was your age, people always said I was like the morning sun. I never stopped smiling.” I tried giving her a demonstration, but she was not looking. Instead, she chose to focus then on picking up her forgotten bowl and discarding it in the sink to join the rest of the dishes from the previous breakfast rush.

“Must have been nice,” said Abby as she trudged back up the stairs to her room, “to have such a supportive group of people around you.” But the acoustics in the living room were never that great to begin with, so I did not hear her.